We often treat hydration as a simple input/output equation: drink water when thirsty, and the body handles the rest. But if we look at the human body from a systems perspective, we realise that “thirst” is actually a lag measure—a reactive signal that fires only after your system is already down by 1–2% in water volume. By the time you reach for that glass, your cognitive and physical performance may already be throttling.

The truth is, true hydration isn’t just about what you drink; it’s heavily influenced by what you eat

A recent comprehensive analysis, Dietary Approaches to Human Hydration, compared the three dominant dietary architectures—Whole Food Plant-Based (WFPB), Carnivore and Omnivore—to see how they impact fluid balance. The results suggest that your dinner plate is just as important as your water bottle.

The Hidden Water Source: It’s Not Just Liquid

The average adult gets roughly 70–80% of their water from beverages. But that remaining 20–30%? That comes from solid food. This is the “hidden variable” in the hydration equation.

Depending on your diet, you are either passively loading your system with water throughout the day, or you are placing a heavier load on your kidneys to maintain balance. Let’s look at how the three major diets stack up.

1. The Whole Food Plant-Based (WFPB) Approach: Passive Hydration

The study highlights that a Whole Food Plant-Based diet offers the most efficient “passive” hydration strategy. This comes down to the sheer water density of the ingredients.

Fruits and vegetables are essentially water in a biological package. Cucumbers and iceberg lettuce are nearly 96% water; spinach and watermelon sit at around 91%. When you base a diet on these foods, you are constantly ingesting water without lifting a glass.

The Electrolyte Advantage:

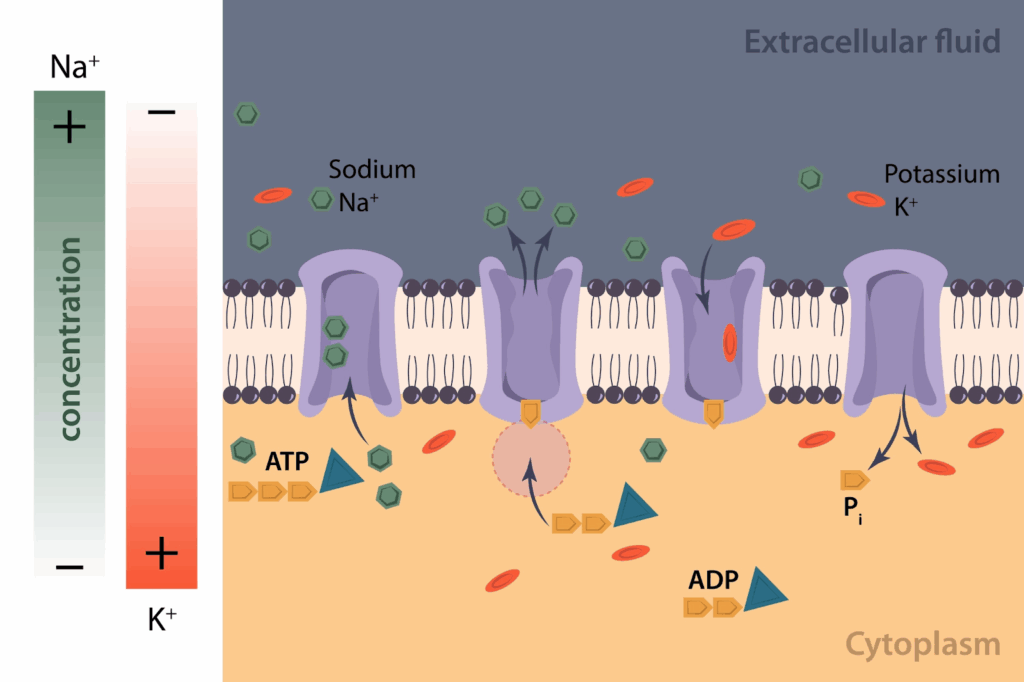

It’s not just about volume; it’s about retention. WFPB diets are naturally high in potassium and magnesium (found in leafy greens, bananas and avocados) while being low in sodium. This specific electrolyte profile encourages water to stay inside your cells (intracellular hydration), rather than bloating the space between them.

Furthermore, the high fibre and complex carbohydrates in this diet help create a reservoir effect. Carbohydrates are stored as glycogen, and for every gram of glycogen, the body stores about 3 to 4 grams of water. This acts as a buffer, keeping you hydrated longer.

2. The Carnivore Diet: The “Active Management” Approach

On the other end of the spectrum is the Carnivore diet—exclusively animal products. While meat does contain water (raw muscle meat is about 75% water, cooking reduces this to 55–65%), the metabolic impact of this diet requires a very different operating manual.

The Diuretic Effect:

The Carnivore diet is typically very low in carbohydrates. Without carbs, insulin levels drop, and the body depletes its glycogen stores. As mentioned above, glycogen holds water. When it’s gone, the body flushes that water out. This is why many people see a rapid drop in “water weight” when starting low-carb diets.

The kidneys also switch gears, excreting sodium and water at a faster rate. This creates a state where you might be drinking water, but your body isn’t holding onto it effectively.

The Fix:

The study suggests that hydration on a Carnivore diet requires proactive management. It’s not enough to just drink to thirst. Adherents often need to aggressively supplement electrolytes—specifically sodium, potassium and magnesium—to prevent “keto flu” symptoms such as headaches and cramps.

If WFPB is an automatic transmission, Carnivore is a manual stick-shift; it offers high performance for some, but you need to pay constant attention to the gears (electrolytes) to avoid stalling.

3. The Omnivore Diet: The Variable Spectrum

Most Australians fall into the Omnivore category, eating both plants and animals. However, the study notes that this is the most variable group regarding hydration health.

The Processed Food Bug:

The biggest risk for the modern omnivore isn’t the meat; it’s the processed food. The “Standard Western Diet” is often high in sodium (salt) and low in potassium.

This imbalance disrupts the body’s osmotic pressure. High sodium pulls water out of your cells and into your bloodstream, which triggers thirst and can lead to high blood pressure, even if your cells are technically dehydrated.

If an omnivore focuses on whole foods—plenty of veggies, lean meats and minimal processed snacks—their hydration status can rival the WFPB group. But if the diet relies on takeaway and packaged goods, chronic dehydration becomes a very real risk.

The Verdict: Optimising Your System

Hydration is a full-stack job. It requires looking at the inputs (food and water) and the processing (electrolytes and kidney function).

Regardless of which dietary protocol you follow, here are three strategies from the study to optimise your hydration:

- Don’t Wait for Thirst: Thirst is a delayed notification. By the time you feel it, your cognitive function may already be dipping.

- Eat Your Water: If you are an omnivore or plant-based eater, load up on “water-heavy” vegetables. If you are a carnivore, recognise that your food volume is lower, so your fluid intake needs to be higher.

- Balance Your Electrolytes: Water follows salt, but it balances with potassium. If you eat a lot of salty foods, you need to increase your potassium (avocados, bananas, salmon) to keep the system in balance.

At the Hydration Health Organisation, we believe that understanding your water—both where it comes from and what’s in it—is the first step to better health. Whether you’re checking the quality of your tap water with our My Water Risk App or adjusting your diet for better fluid retention, knowledge is your best filter.